Start 14-Day Trial Subscription

*No credit card required

How Are Hops Grown and Harvested?

Beer lovers know that hops are the most important element of any good brew, but how are hops grown and harvested? Let's delve into a hop harvest in the Willamette Valley to provide the answer.

The Harvest

Third-generation hop farmer Gayle Goschie can finally rest. The harvest is over. The Crystal Zwickle pale ale from Central Oregon’s Crux Fermentation Project tastes of freshly zested oranges and fresh-cut wood, which is to say it tastes amazing and vibrant. That’s because the Crystal hops used in its making were still growing at Goschie Farms in Silverton, Oregon the very morning the beer was brewed.

It was a pretty good year for hops. But that’s not always the case.

“Hop farming is hop farming, and how my grandparents farmed to produce the annual harvest and how I manage my crops are very similar: boots on the ground, working with Mother Nature. I thought for a time that I could manipulate or manage the big Mother, but no, she rules. One late spring day after I had returned from college for the summer work season we had a freak hailstorm flatten a 20-acre field of hops. As we stood at the edge of the field discussing our options to save the crop, the conclusion was reached that nothing much could be done. I was instructed to simply wait for the plants to regrow new shoots and then retrain those shoots up the network of strings.”

(Photo Courtesy Crosby Hop Farm)

(Photo Courtesy Crosby Hop Farm)

For almost as long as there have been European settlers on American soil, there has been European-style beer. And on the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s push for brewing beer with wild hops instead of other herbs and flora (which is a story for another day), it’s important to know just how hops get into our beer today since it’s an industry unto itself. In fact, according to the Hops Growers of America, the first commercial hop farm was planted in 1648 (yes, near Plymouth Rock). Today, some 45,000 acres of farmland are devoted to humulus lupulus, the fragrant flowers that add much of the flavor, aroma, and bitterness to beer. Most U.S. hops hail from the Pacific Northwest (because summer days are longer and the fertile soil gets tons of rain). Washington, predominantly in the Yakima Valley, accounts for 70 percent of our hops while Oregon, predominantly in the Willamette Valley, grows another 15 percent. All the small hop farms from Michigan to New Mexico are nice for their respective local breweries, but even combined they do not equal Willamette’s 7,000 or so acres.

Goschie Farms accounts for 550 of those. Crosby Hop Farms down the road in Woodburn adds another 350 acres. Between Gayle Goschie and Blake Crosby, these two modern hop growers and their ancestors combine for 250 years experience keeping brewers, and beer lovers, in hops. Each acre will, on average, yield 900 plants that in turn will generate some 2,000 pounds of dried hop cones. And from the last second they have to grow in the field come September, within 32 hours each cone will be brewery-ready.

Finding Hops A Home

Hops can be sold directly to a brewery, or through a distributor, both of which will contract with the hop grower in advance. Bruce Wolf, owner of St. Paul, Oregon-based hop distributor Willamette Valley Hops, comes from five generations of hop growers.

Having spent his entire life around hops, he knows what to look for when sourcing product.

"It's important to know where your product is coming from," Wolf says. "There's no "book" on hop growing, and almost every farmer is going to treat their hops differently based on what knowledge was passed down to them."

"A lot of the process is visual – I get to watch these hops grow every summer, because the farmers that our supplier buys from are all around me. You're able to compare by look, the way the fields are maintained, the money spent in doing so, and it all reflects on the final product – the hop cone. It's still real old school – when we look at hops we're still walking in the fields, ripping hop cones down, smelling them, looking for seeds. It's very hands-on."

Unlike most distributors, Willamette Valley Hops focuses exclusively on small brewers, 25,000 bbls or less, essentially making the business a craft supplier. As such, personal relationships come to the fore, both with hop farmers and brewers, including many of the country's top Hazy IPA brewers.

With the hazy IPA style as an example, Wolf notes the ability of the consumer and their leverage of social media to dictate what a hop supplier might stock. As a result, hop growers and suppliers "have to keep their finger on the pulse" of what's hot. Hop suppliers must understand not only how hops are grown, but how they will affect a beer.

"As a supplier, brewers will call us asking what hops to use, which has really helped expand our knowledge of brewing. If a brewer wants a New England-style IPA, we have a few hops that can actually add haze to the beer."

In this way, hop growers and distributors play a vital role in the brewer's creative process.

"When a brewery wins a medal for a beer we supplied the hops for, that's gratifying. So there's a kind of unspoken appreciation we have for the brewer. Not everyone in the sales business gets to turn around and try something made with their product that they enjoy."

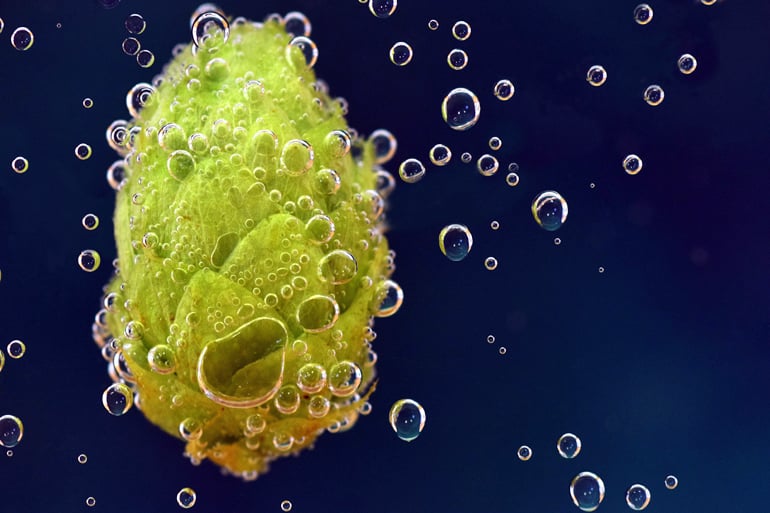

How Hops Are Harvested

First, a bottom cutter clips plants (called bines) at their base. Next, 18 feet above the dangling bines, a top-cutter comes along and cuts them from atop the trellis where they fall into a truck. Once out of the field, they’re first processed on a hop-picker and moved by conveyor belt through the main picker (at the pace of 20 bines per minute). Hop cones are separated from all the leafy material with vertical screens that turn upwards in motion as well as fans that blow against the screens. As the collection of cones and leaves are let to fall from above, the air from the fans blow the leaves flat to the screens and are carried up to become compost. From there, the final process of hop separation are dribble belts where our little, green, pungent friends dribble down a series of belts that slowly turn (while the leaves, stems are carried on). After a roughly 250-foot journey along all these belts, the hops reach the dryer floors to be kilned. Hops are dried with forced air pushing through 24-inch beds of hop cones at an average temperature of 130 degrees for up to eight hours. Lastly, the dried hops are moved to a cooling area—a big empty room where they’re distributed out and blended (one varietal at a time) for homogenization since each individual hop may posses a variance in cherished alpha or beta acids.

Fascinatingly, one critical element of this cooling period has to do with residual moisture levels. As fifth-generation hop grower Blake Crosby points out, “Too high moisture creates anaerobic conditions. Moisture can create (essentially) spontaneous combustion; it generates its own heat as if it’s composting.” When asked if he’s ever witnessed this, Crosby says he hasn’t, “but it’s in the record books. Quite a few hop fires and bale or warehouse fires have erupted.” Luckily, the industry on the whole has learned from this and it typically hasn’t occurred in over a decade.

The whole harvest lasts just one month, but it’s a 24-hour-a-day, six-to-seven-day-a-week effort. Goschie Farms had 45 sets of hands and Crosby had over 35. Yes, there’s some mechanization today that occurred after World War II, but it’s still a dirty-hands operation that takes a communal effort. Maybe in the future it’ll become more automated. But come springtime, when it’s time to begin pruning and twining the hop shoots in advance of next year’s harvest, it’ll be done by hand. Of course, their end product is the beer you get to hold in your own hands, until the fun mouth part comes along and you get to drink those hops.